The world of work has undergone significant changes over the past 30 years. Performance targets, accountability reports and psychosocial risk factors aren’t things we would have heard much about prior to the 1980s. Today, however, they are part and parcel of a growing number of workers’ daily lives.

The world of work has undergone significant changes over the past 30 years. Performance targets, accountability reports and psychosocial risk factors aren’t things we would have heard much about prior to the 1980s. Today, however, they are part and parcel of a growing number of workers’ daily lives.

Alienation in the workplace

Let’s take a look at how things were from the 1940s up until the 1980s. Back then, there was one prevailing work model, known as Taylorism, which could be summed up as fragmented, repetitive and mind-numbing factory work which did not afford workers any opportunity to demonstrate initiative or creativity. Any and all directives would come from the top and employers exerted significant control over their employees. Work, which usually revolved around an assembly line, was synonymous with alienation.

Nonetheless, thanks to unionization, working conditions began to improve, particularly with respect to wages, benefits, vacation time and sick leave. There was also a steady decrease in working hours, from an 84-hour work week at the turn of the 20th century to about 35 hours per week in the early 80s.

Working for the same company throughout one’s life was almost a given for workers in those days. And so, in exchange for an alienating job that offered little chance of fulfilment, they agreed to good working conditions and job security.

A significant shift

The early 80s mark the arrival of a far-reaching shift: globalization. As commercial markets open up, the world of work undergoes a fundamental change.

The early 80s mark the arrival of a far-reaching shift: globalization. As commercial markets open up, the world of work undergoes a fundamental change.

Industrialized countries, such as Canada, and their working conditions, must now contend with the poor working conditions of emerging countries. Companies bring down their production costs through various means: relocating operations in other countries, making jobs less secure, subcontracting and demanding significant concessions with respect to working conditions.

The organization of work also undergoes significant changes. To better address an ever-changing economic landscape, employers are looking to broaden their employees’ skills. The ability to take on various roles within an organization, mobility and the ability to work out various issues are some of the more sought-after qualities. Organizations are asking their staff to adapt to any situation and take on greater responsibility with regard to the quality of the products and services they provide.

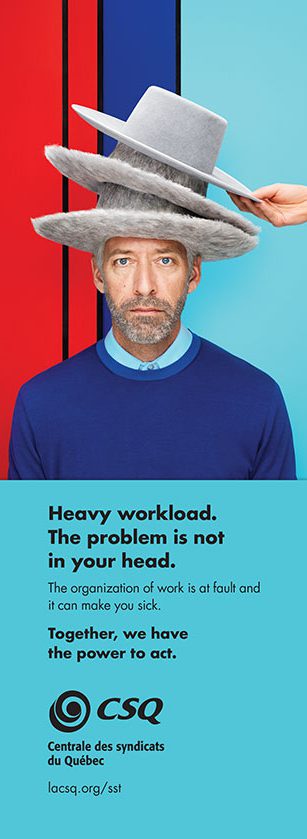

Though they might be conducive to greater autonomy and creativity, these new forms of work organization also leave the door open to a variety of issues, namely heavy workloads and a faster work pace. Tasks are also becoming considerably more complex.

What about the public sector?

In this context, the government is expected to play its part and perform efficiently. To this end, there are fewer and fewer resources allocated to serve the population in order to cut costs. Employers subcontract and cut jobs and, in doing so, lose some expertise.

In both the education and health sectors, organizations adopt management approaches that stem from the private sector, and set performance targets. These management approaches focus on cutting costs, at the expense of the quality of the services being provided. We’ve even seen a shift in the terminology. Recipients of public services are no longer “users”, but “clients”.

Who’s to blame?

These management models, combined with constantly diminishing resources, have significant implications for working conditions. For instance, the substantial increase of heavy workloads, a result of intense and complex tasks, leads to stress, burnout as well as symptoms of depression and anxiety.

These management models, combined with constantly diminishing resources, have significant implications for working conditions. For instance, the substantial increase of heavy workloads, a result of intense and complex tasks, leads to stress, burnout as well as symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Tackling both an increased workload and decreased work autonomy, workers struggle to provide services that are sufficiently laudable for them to feel a sense of professional satisfaction. Even worse, they question their own skills: “If I can’t manage to perform well in my workplace, am I to blame?”

Managers believe that the root of the problem lies in individual adaptation issues. They are convinced that if their employees really tried, they could rise to the challenge and provide quality services at the lowest possible cost. But they are wrong!

To protect themselves, workers in the public sector turn to therapists or ask their doctors for antidepressants and antianxiety drugs. Others go on sick leave. Some abandon the profession outright, convinced that their workplace will never provide working conditions that are both acceptable and respectful of their personal values.

And yet, studies clearly show that the problem lies with work organization rather than individual performance. Management methods developed in the private sector completely disregard the public sector’s distinctive characteristics. You simply cannot run an institution, operating in the education, health or childcare sector, as if it was an assembly line. Moreover, there isn’t enough personnel to handle all the work that needs to be done.

Our power: action!

In light of the challenges experienced in their workplaces, CSQ members in attendance at the June 2018 Congress voted for orientations under a collective action theme. By working together, rather than acting individually, we will achieve tangible results which will allow us to:

- Understand what we are experiencing in our workplaces and finally be able to pinpoint what’s wrong.

- Articulate the values which underlie the work we do and services we provide to the population.

- Develop a collective project asserting these values, and share it with the public, parents, advocacy groups, users, etc.

- Implement actions to effect change in our workplaces.

- Ensure that public services go back to being services for the citizens, rather than commodities from a purely financial perspective.

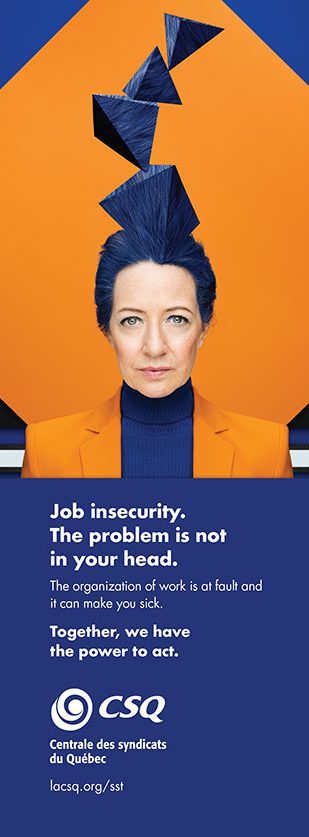

In short, as our latest campaign so aptly puts it: “It’s not in your head! The organization of work is at fault and it can make you sick. Together, we have the power to act.”